By Ken Dilanian

![]()

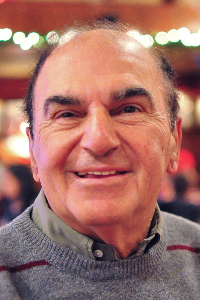

A decade and a half ago, my father got devastating news: He had a form of blood cancer called myelodysplastic syndrome, or MDS. He didn’t qualify for the only cure, a bone marrow transplant. He had three years to live.

It was one of the few times my sister ever saw him cry. But that didn’t last. His congenital optimism reasserted itself as he threw himself into whatever might help, from eating pineapple to weekly blood transfusions.

Last month, at 88, he walked unassisted up the bleacher steps to watch my son play high school football. A few days later he played nine holes. Doctors, schmoctors.

Ken Dilanian’s defiant run ended this week. Vaccinated against COVID months ago, he succumbed after a month in the hospital to a more run-of-the-mill infection with an equally cruel outcome.

But he slipped away a happy and contented man, at home, surrounded by his four grandchildren and nearly everyone else who loved him.

“Dad, what are you thinking about?” I asked him towards the end, when it was difficult for him to speak. “Game… Over!” he replied.

“Are you sad?” I pressed.

“No!”

He was not a religious man, nor particularly introspective. His religion was reason, a positive outlook, and the promise of America.

He lived a quintessentially American life.

The youngest son of Armenians who fled Turkey for Boston ahead of the 1915–1917 genocide, Dad enjoyed a childhood in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood that was the product of what we might call extreme free-range parenting. A skinny, undersized kid, he rode the subway by himself at 8 years old, played stickball on the street, and snuck into Fenway Park. Later, he would put on a jacket and tie and go to the Copley Plaza Hotel to beg autographs from famous ballplayers, believing a presentable appearance would improve his chances.

He remembers where he was when he heard the news that Pearl Harbor was attacked, and also waiting in line to buy a ticket to Game Six of the 1946 World Series, only to watch the curse persist as the Red Sox fell to the Cardinals.

Having lived through the end of the depression and World War II rationing, he once saw his father return home with a broken jaw when, desperate for work, he crossed a union picket line. “You have no idea what it is to be poor,” he once barked at me in a rare flash of cold anger, ending an argument about money.

His father was a tough man. Turned away by the U.S. Army at the onset of World War I, he joined an Armenian unit of the French foreign legion and served in Egypt as a combat medic. That devotion to the Allied side smoothed his way to U.S. citizenship despite the fact that he didn’t speak a word of English. My more refined grandmother, fluent in five languages, raised her three kids to believe they could do anything because the opportunities here were limitless — even for the sons and daughters of factory workers who looked and spoke differently. Dad’s older sister was one of the first female stock brokers on Wall Street.

In his teens, he held a series of old timey jobs he would recite to us over the years with pride: Soda jerk, meter reader, movie usher.

He was the first person in his family to go to college. After getting an undergraduate and law degree, he did his military service as a clerk in the Army’s ceremonial Old Guard regiment, standing at attention for President Eisenhower. He used the GI bill to get an MBA.

He spent a career in life insurance, but his passion was politics and current events. His shelves were filled with nearly every book about Watergate ever written, even though he wasn’t much of a long form reader. He is the reason I became a journalist, because he kindled that interest in me almost as soon as I could talk. We watched the Nightly News and the Sundays shows together for years. He used to call himself a Scoop Jackson Democrat, though only political junkies like him remember the center-left Cold Warrior from Washington State.

Dad spent the last four years disgusted with how the White House occupant and his enablers shattered post-Watergate norms, but he never lost faith in the America that provided the tools for a son of impoverished immigrants to carve out a comfortable middle class life — and opened to his children opportunities his own parents could not have imagined.

When he couldn’t stomach the news, he always had his beloved Boston sports teams. In the DVR era he began recording every Red Sox game so he wouldn’t miss an inning.

Early in his corporate career, back when business travel was glamorous, his job took him to nearly every city in the country — building his appreciation for America. And on a summer weekend in Cape Cod, he met my mom, a New Jersey farm girl teaching elementary school in Boston. They started their married life 90 miles west, outside of Springfield, where his suburban existence included service as president of the neighborhood association, an adult hockey league and a weekly engagement with a lawn mower — after which he would drink a Miller Lite, sitting in a leather recliner.

We weren’t affluent. I didn’t fly in an airplane until I was 18. But when I failed most of my of classes during my senior spring and was dis-invited to Wesleyan University, my crestfallen father took out a second mortgage to pay for a post-graduate year at boarding school. “Best thing that ever happened to you,” he would always say, and he was right.

I was thinking of that episode when I whispered in his ear, near the end, to thank him for always being there to help me up when I fell.

In 1991, the life insurance company where he toiled in middle management for 32 years collapsed. He was 59. He lost 10 pounds from the stress, sent out more than 500 resumes, and finally landed a job at another insurance company in upstate New York. My mother was getting cancer treatments, so he spent the next eight years living in an apartment during the week and coming home on weekends, boosting New York State coffers with his speeding fines.

Just in time for his retirement, mom died. He had spent every day in the hospital with her for two months as she faded. But his grief could not shake his fundamental worldview: Keep moving forward. A second chapter of his life began.

First came years of travel that wasn’t possible with his ailing wife. For part of that time I was working as a foreign correspondent based in Rome, and he met us for vacations all over the world, including to his mother’s old neighborhood in Istanbul. One particularly memorable moment came after a knock on the door at a hotel overlooking the glittering lights of Bangkok. There stood a grinning dad, holding his golf bag travel case, having just flown 24 hours around the world.

After his MDS diagnosis, he moved in with my sister, Jane Reitz, and her family, in a row house in the dense urban neighborhood of Charlestown, steps from the Bunker Hill Monument. It’s hard to overstate how much that change enriched the last 12 years of his life, and theirs. He became a third parent to Jane and Allen’s two kids, Charlie and Emma; a fixture at dinner parties; and an even more accomplished traveler, hiking the mountains of Costa Rica and the streets of Barcelona. He volunteered at the local elementary school.

Our mother never knew Charlie and Emma, nor my children, Kenny and Max. She never met my wife, Cathy. Dad saw his legacy bloom in the next generation. And he got to watch his Red Sox break the curse, and then some. What a gift.

In his eighth decade he fought through a series of health setbacks but remained as upbeat as ever. At his 2019 birthday dinner, he told his grandkids, speaking in his native Bostonian, that the secret to a happy life was “paaw-zitive mental attitude.”

When the doctors at Mass General told us last week he appeared to be hours away from death, we brought him home for hospice care. Dad confounded the experts one last time. He ate sorbet, drank beer, watched the Sox and the Celtics — and lasted four days.

In one of his final moments of lucidity, he called his four grandchildren together around the hospital bed we had placed his living room and exhorted them to look out for each other.

“We all love one another, but talk is cheap,” he said.

We will miss him so much. But it was a good American life.

A CELEBRATION OF LIFE WILL BE HELD AT A LATER DATE, PLEASE CONTACT THE FAMILY FOR MORE DETAILS.