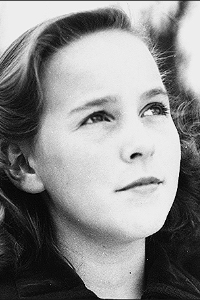

Counselor, Quiet Champion of Truth and Beauty

A friend to strangers and the young, Katherine Andres Moore, a daughter of Brookline and partner to the late American diplomat Jonathan Moore, died peacefully at her home in Weston on March 24 after a brief illness. She was 84.

Clung to to the end by her friends and family for her sincere sweetness and empathy, Mrs. Moore – Katie to her friends – kept faith with her first passions of family and fairness in the world for the three years after her husband Jonathan died, but betrayed signs starting at the end of 2019 of wrapping up the projects of this last period to resume her favorite concern, a collaboration with the greatest of her loves, Jonathan Moore.

"I truly believed that Katie had said good bye to me for the last time when I saw her in December," Shirley Registre, a member of the staff at Newton-Wellesley Hospital and a friend, wrote in a recent e-mail. "From the way she looked at me and hugged me, to the blessing she gave me at the end by gently touching my forehead, I felt Katie knew her time to journey on was near, and that she was content."

A beloved yet self-effacing student leader in her nine years at the Beaver Country Day School, which she walked to from her family home in the Brookline section of Chestnut Hill, Mrs. Moore received a Bachelor's degree in English from Smith College in May of 1957, and had planned to teach English. But her first notions of how she would work with the young were transmuted by an invitation to the Dartmouth Homecoming her senior year by the son of an old associate of her father's.

"You may not want to marry him, but he will be a lot of fun," her father, F. William Andres, advised her about the recent Dartmouth graduate, Mr. Moore, whose father Charles a generation earlier had been Mr. Andres' summer counselor at Camp Becket in western MA, and was himself a senior at Dartmouth when Mr. Andres first enrolled at the same school.

Mrs. Moore did hesitate in marrying Mr. Moore, but not for the reasons her father had implied.

"I thought the marriage might be short," Mrs. Moore often recalled. "We were so different." Mr. Moore was assertive and intellectual, Mrs. Moore, intuitive and a nurturer.

When during the couple's engagement they visited Mr. Moore's family in Orleans on Cape Cod and Mrs. Moore went to bed one night having pronounced her reversal on her agreement to marry Mr. Moore – according to legend, the entire Lower Cape shook. Calm returned when Mrs. Moore completed her 360 the next day. (The couple married the June following Mrs. Moore's graduation from Smith.)

While so many of her friends' first choice as the best example they knew of unfailing devotion and support to a partner – Mr. Moore, whose vivid and esteemed career of public service took the couple from tours of India and Africa, to foreign policy and domestic federal posts and Mr. Moore's signal twelve years as the longest-serving director of Harvard's Institute of Politics, Mrs. Moore was not only perhaps the sine qua non of Mr. Moore's celebrated career, she was her own person.

"Crazy as I was for Jonathan, I was somehow blessed with an important objectivity about him," Mrs. Moore said.

After once observing well into the marriage how difficult Mr. Moore found Mrs. Moore's not agreeing with him on a matter of consequence, she realized she brought at least one quality to the relationship in apparent greater measure than he did – a capacity to retain her identity outside of it. Yet, like so many of her strengths, she neither crowed about that unequal power, nor exploited it overweeningly to her own advantage.

And in Mr. Moore Mrs. Moore had found not just a person with whom she identified but the values of identifying with everyone. Consonant with Mr. Moore's very visible stances of courage supporting his boss Attorney General Elliot Richardson in Watergate's Saturday Night Massacre, or of commitment to the human individuals endangered around the world in his years as President Reagan's U.S. Coordinator and Ambassador for Refugee Policy, or those he simply encountered face-to-face in his own community, Mrs. Moore sided with others, writing recently in support of the values of a young friend applying for admission to the Massachusetts Bar: "The huge gap between the rich and the poor in this country and in the world needs to be radically reduced, and each individual human being deserves the right to freedom, respect, and fairness."

Mrs. Moore was born May 24, 1935, in Boston to Mr. Andres, a labor relations lawyer, and the former Katherine Weeks, a homemaker and member of Boston's Junior League. In addition to her three daughters, Joan Brooke of Abiquiu, NM, Jennifer of Albuquerque and Jocelyn Moore Clinton of London, and her son Charles IV of Weston, Mrs. Moore is survived by her younger sister, Anita Andres Rogerson, of Woodstock, VT, and four grandchildren. Her younger brother William died last year. Memorial arrangements for Mrs. Moore have yet to be announced.

Mrs. Moore's commitment to others began with young people, starting with her own four children, each of whom in her eyes surpassed in their lived lives the individual excellence she first spied in each, and for whom she never gave up the activity of worrying over their difficulties or summoning her maximum imagination in formulating for them support in their professional, artistic and emotional lives.

And for Mrs. Moore a celebration and encouragement of art – a thing undercredited in her own crafting of language in letters or the color of a bedside flower or detail in a meal – was not in addition to her encouragement of other people but arguably a seamless part of it, and her faithful seeking out and holding up of the beauty and truth of reality.

Faithful to her original resolve to teach, starting overseas before raising her children and resuming in earnest after that, Mrs. Moore was a mostly volunteer but sometimes paid tutor and counselor to other people's children, most often poor and minority.

Paired in the early 1980s with Bruce MacDonald, the principal of Weston High School, (from which all four of her children graduated), she helped lead one group of weekly evening discussions in rotating homes with willing high school juniors and seniors on matters of importance to them. That began a series of informal engagements Mrs. Moore made leading adolescents in discussions about values and relationships in the District of Columbia after Mr. Moore returned to the State Department in 1986, at Rikers Island Prison in New York when her husband was a U.S. deputy ambassador to the U.N. from 1989 to 1993, and in Roxbury through a program run by Weston's First Parish Church after Mr. Moore left direct work for the U.S. government.

But while Mrs. Moore was arguably a heavyweight on paper, her greatest genius was something that was truly realized probably only through direct observation – an intangible quality perhaps clearest to those encountering her for the first time, from all communities, something that might simply be described as the faithful and authentic response to others of love and friendship and the crucial attributes of warmth and kindness, a phenomenon not infrequently experienced through the very simplest but sincere and mindful of gestures.

Helen Clinton Lall, one of Mrs. Moore's daughter Jocelyn's two sisters-in-law, recalled a story of Mrs. Moore recently to Mrs. Moore's son Charles: "I had been in Weston one evening and your Mum and I were in the kitchen and I shared with her how much I wanted to become a mother. Then she called me while I was still in the hospital after Sameer's birth to tell me how happy she was for me. It meant the world to me, and I will never forget it."